Nothing But Longing, Void Art Centre and the LD50 Gallery controversy

This isn’t a review of a show I haven’t seen. It is, rather, an attempt to bring together two events that occurred over the last few months, AFK and online, that may be seen as part of an ongoing international conversation – into which I insert a modest, local take.

On the 14th of January, ‘Nothing but Longing’ opened in Void Art Centre. This exhibition, curated by Sagit Mezamer, comprised the work of emerging Israeli artists who had each been on residencies in the Curfew Tower in Cushendall, County Antrim. The Tower is owned by artist and provocateur Bill Drummond, who wrote in the Guardian in 2014 about the impetus for this project. He describes the expression of international political sympathies and assumed equivalences that are made visible through flags and murals in the North: nationalist / republican areas display Palestinian flags and Israeli flags are flown in unionist / loyalist areas. For Drummond, the decision to programme a year of Israeli artists’ residencies in nationalist / republican Cushendall was a way of challenging a received narrative of ‘baddies and goodies’, in order to foster dialogue across seemingly insurmountable divides.[1]

Drummond’s ‘contact hypothesis’ approach will be familiar to those who have any experience of working in the arts or in the community in Northern Ireland. It is a truism that the way to resolve intractable conflict is to bring groups of people together to engage in some sort of equal exchange of ideas. The underlying assumption is that the parties involved are not operating from a rational political position, arrived at through logic and ethics, but are in thrall to a tribal mindset that can be challenged, and ultimately cured, through contact with one another.

Void made some efforts to mediate the way in which this project would land in largely nationalist / republican Derry. They spoke to the local Ireland Palestine Solidarity Campaign (IPSC) in advance of the show and organized a panel discussion towards the end of the exhibition with Drummond, Mezamer, artist Raymond Watson and Becca Bor, a representative of IPSC, who spoke about the Boycott Divestment Sanctions (BDS) movement. While the agenda of ‘Nothing but Longing’ funder, Artis International, appears to align closely with the artwashing of ‘Brand Israel’, Void also provided a blanket disclaimer that the project “was not supported by funding from the State of Israel and all the artists in the exhibition condemn the occupation of Palestine by Israel.”

Elsewhere, in February, the London-based artist Sophie Jung made public a series of private messages between her and Lucia Diego, the director of the LD50 gallery in Hackney, related to the alt-right nature of the gallery’s exhibition and public programme as well as the general character of LD50’s online presence. Their exchange and the subsequent deluge of commentary from artists and others went on to launch a flotilla of think pieces about, variously, the need to root out fascism from the art world; the sacredness of the free exploration of ideas; the fact that we (artists, curators, critics and institutions) are all already deeply implicated in a system of uneven privilege and access, and so on.

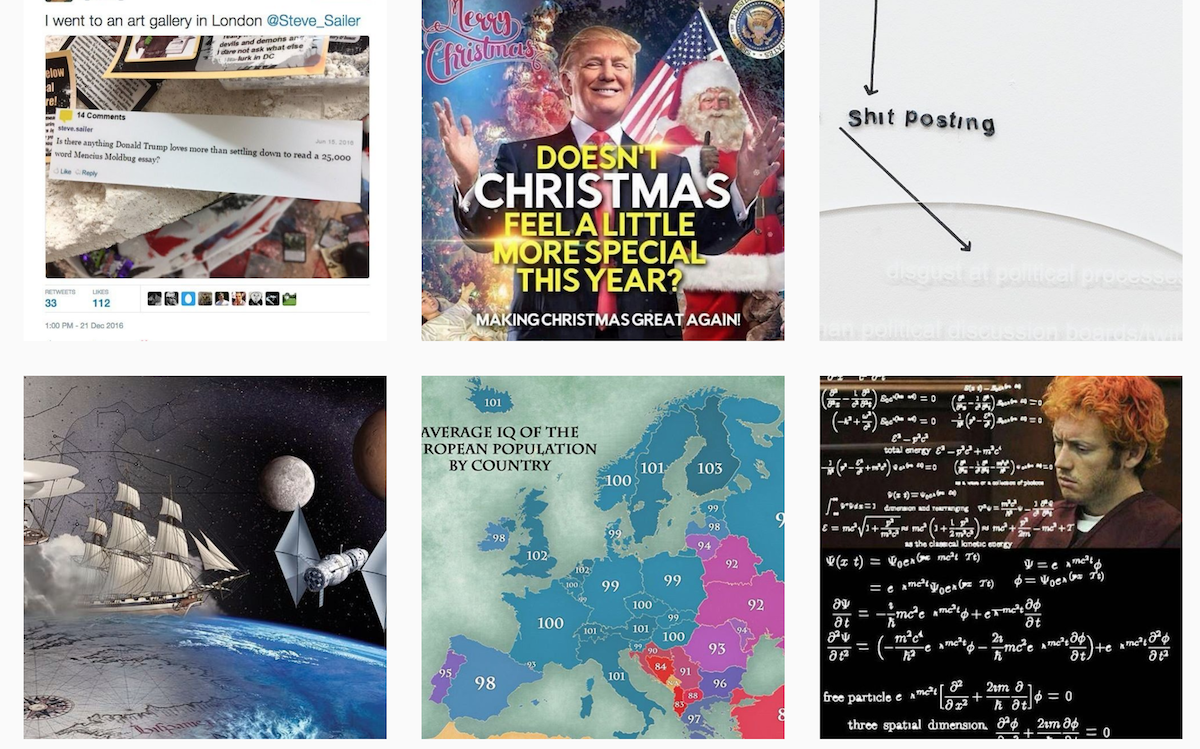

Of course, if LD50’s programme had been platforming unadulterated fascism, it would not have had the power to inspire such a flood of response. Instead, exhibitions exploring, for instance, the “Alt Right, male frustration, Neoreaction, spirit cooking, Pepe, Kek, the occult and the rise of memetic communication” were embedded in their programme alongside exhibitions by respected artists including John Russell, Jesse Darling and Joey Holder. At the time of writing, millions of keystrokes have been expended in critique and counter-critique of the initial exchange, LD50’s programming strategy, and what it means for the future of artistic ethics, freedom, and inquiry.

There is no exact formula to find this edge – between promoting the free circulation of concepts, meanings, artists and dialogues; and tacitly endorsing them by providing a platform for their legitimation. Whatever calculations are made must include questions of social, political and economic context, of timelines, of political efficacy and the personal ethical limits of the individuals involved.

Art is a field of knowledge that takes speculation, ambiguity, and doubt as its epistemological foundations, but these foundations can also become doctrines that are used to shut down discussions about the renegotiation of power. As discourses around decolonising and queering, for instance, find new traction in the ways we think about art, perhaps it is inevitable that there will be some sort of pushback. That pushback may take the form of the establishment of alt-right project spaces or it may take the form of programmes that rehearse, without much thought, narratives of equivalence and reconciliation. It would be great to emerge from the discussions prompted by these events clearer about how we can act in our own spheres of influence, in ways that are more holistic, complex and reparative.